- Home

- Rachel Vorona Cote

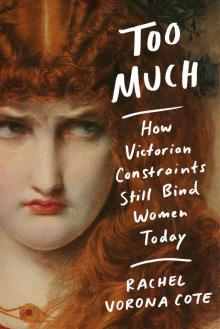

Too Much Page 2

Too Much Read online

Page 2

We’ve long understood that masculine experience is posited as universal, or at least as more compelling (women are not necessarily invited to relate to John Rambo, but then, the Rambo franchise, like so many cultural entities, was not created with us in mind). It is also the case that, from childhood, we are all of us instructed to revere stories of boys becoming men—in the most conventional sense—while the feats of others, particularly women, are understood as so exceptional as to nearly be taken as fiction. Moreover, bravery that wears a feminine face is rarely applauded without the lurking question of whether it should exist in the first place—Disney’s Mulan (1998) is one such example. Though we cheer for her, it is always our understanding that her adventures, should she survive them, will end. Eventually, she will return home, to her parents, and reassume the mantle of dutiful daughter. And what luck: dressing in drag, joining the Chinese army, and nearly being slaughtered—both for breaking the law and by the Hun army—results in her snagging sexy soldier Shang (whose over-the-top masculinity and verve is presented as both inspirational and, for a children’s film, weirdly titillating).

Then of course there are the scattered shards of popular culture that reify privileged male excess in more granular and mundane ways. After all, one need not—and probably should not—go full Rambo to enact hypermasculinity. When I was an undergraduate in Virginia, and AIM profiles operated as intertextual self-endorsements, the chorus of the Dave Matthews Band’s 1996 hit “Too Much” made the rounds as a cyber-epigraph. Its inclusion seemed a choreographed shrug in the face of debauchery, a barely coy means of expressing, through performed pseudo self-deprecation, that one was living the good life of Pabst Blue Ribbon, Wawa hoagies, and boozy, wet kisses.

Ultimately—and this is the logic upon which the song turns—we expect men to be hungry and horny and to wet their whistles with a beer or five; we overlook and even giggle at their vices. Gleefully, ravenously, Matthews sings, “I eat too much / I drink too much / I want too much / Too much.” What strikes me most about this debauched anthem is how it deploys the rhetoric of self-critique in order to revel in a prism of desires: food, booze, sex, merrymaking. Matthews acknowledges—celebrates—his gluttonous passion; his insatiability is championed by a melody both vigorous and urgent. He is the fraternity brother’s composite of the Heat and Snow Misers from The Year Without a Santa Claus, announcing with cheery gusto, “I’m TOO MUCH!”

And while it’s reductive to designate experiences as either “masculine” or “feminine,” Dave Matthews’s iconic status among twenty-something men is by no means coincidence. Nor am I surprised that the lyrics to “Too Much” tended to populate the profiles of the male college students with whom I was acquainted, rather than those of their female counterparts—though, admittedly, I think I may have posted them at some point. (I had a brief, strange love affair with the Dave Matthews Band that I entirely blame on my Virginian upbringing; the band assembled in 1991 at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.) For the Dave Matthewses of the world, “too much” is associated with power and virility. But for women—for whom excess is constantly tethered to some perceived lack of emotional or physical control—the concept of “too much” carries the unwieldy baggage of cultural stigma. As Jess Zimmerman writes in her 2016 essay “Hunger Makes Me,” “A man’s appetite can be hearty, but a woman with an appetite is always voracious: her hunger always overreaches, because it is not supposed to exist. If she wants food, she is a glutton. If she wants sex, she is a slut. If she wants emotional care-taking, she is a high-maintenance bitch or, worse, an ‘attention whore’: an amalgam of sex-hunger and care-hunger, greedy to not only be fucked and paid but, most unforgivably of all, to be noticed.”3

Accordingly, when we tell a woman she is “too much,” it is not with the grin and playful tap that the Dave Matthewses of the world smugly expect, but with a wagging finger and the intonations of a warning. Remember that you, and your desires, must be small—diminishing—preferably nonexistent. Ask only for that which you are invited to receive, which is to say, basically nothing.

And yet, Americans are bathed in economic excess, our lives marshalled by it. Capitalism is defined by overabundance, set to a score of “more and more and more,” a yen gurgling in its belly to create and destroy with the sloppiest strokes of greed. The fashion industry, despite some recent fragmental efforts by brands to embrace “sustainability,” has long urged avid, bottomless consumption through the proliferation of fast fashion, garments meant to be both bought and tossed on a whim, within months. But for these companies, the prevailing ethos has been one that turns on extravagant production and wallets coaxed open by savvy marketing—that we owe it to ourselves to gorge on knitwear and stilettos, that greed is self-care. We owe it to ourselves, although the fashion industry, if it continues apace, is likely to gobble a quarter of the planet’s carbon supply by the year 2050.4 Female hunger, when driven by consumerist fantasies that fill the coffers of the wealthy, is—sometimes—more palatable.

Our excesses are stridently policed in this way: when in the service of a capitalist hegemony, they may be overlooked or excused—even when, in certain cases, they ought not be—and sometimes they may even be encouraged. But to be “too much,” as I define it, connotes a state of excess that either directly or indirectly derives from an emotional and mental intemperance: exuberance, chattiness, a tendency to burst into tears or toward what is typically labeled mental instability. In the last several years, the colloquialism “extra” seems to have become something of a near neighbor, although without quite the same bite and with more of an emphasis on absurd or flamboyant behavior than on one’s vulnerabilities or deviations from normative behavior. Often too muchness carries a significant emotional component, because excess, whatever form it takes, is conceived of as a basic function of unbridled feeling. Women who are taken to task for inhabiting unruly bodies, particularly those marked as fat, face stereotypes of immoderacy: on the one hand, they are castigated for not simply choosing and committing to weight loss; on the other, they are lampooned as people constitutionally unable to regulate their appetites. In the eyes of patriarchal medicine, women are endlessly diagnosable, and yet the verdict is always the same: we are fat or horny or skinny or depressed precisely because we are women, and women—that broad, rangy, insufficient category—are predisposed to all manner of prodigality.

Demolishing capitalism and patriarchy are, alas, beyond the reach of this book. We can, however, take stock of the social corset that encircles those of us seeking to live in ways that are deemed inconvenient or messy—or, in the most extreme cases, altogether unacceptable. We have acquiesced to a climate that is hospitable to a statistical minimum, while the margins heave with the rest of us, the Too Much people: humans straining for breath in a milieu that has constricted our air supply, who may be uncomfortable to countenance or even contemplate—that is, if we are to live in the world the way that is truest for us. Now, we inhale and exhale with big, ravenous gulps, urgent and socially verboten. We must take them anyway, these caches of oxygen and sweeps of space: breathing in, shrieking our exhales.

Why the Victorians?

This book draws significantly from nineteenth-century literature and culture, grounding its discussion in a historical period when women’s too muchness underwent vigorous medical scrutiny, routinely receiving a specific, vexed verdict—one that had already dogged women for centuries and that would continue to haunt those of us who live with mental illness or who so much as manifest acute emotional intensity: hysteria. The Too Much diagnosis par excellence, hysteria became an especially ubiquitous catchall for women in the nineteenth century when doctors like French neuropsychiatrist Pierre Janet and American physician Frederick Hollick took grandiose measures to explore the so-called disease’s symptoms and treatments. (Others, like British doctors Robert Brudenell Carter and F. C. Skey, doubted the existence of hysteria, not because they were sympathetic to women, but precisely the opposite: they believed those wh

o complained of symptoms to be both duplicitous and solipsistic.)5 Janet’s work in particular—he posited hypnosis as a preeminently effective means of both study and therapy—manifests itself as an antecedent to Sigmund Freud’s mode of psychoanalysis, which catalyzed the psychological theory of hysteria.6 Hysteria, however, has endured in the medical and larger cultural imagination long after Freud’s hypotheses surrounding penis envy and psychosexual complexes: it was listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders until the third edition was printed in 1980. And even now, its influence is everywhere present, not only distorting prevailing conceptions of femininity but maintaining its antiquated status as a pre-existing medical condition—at once a symptom and a diagnosis.

To be sure, hysteria was not born with the Victorians, although, as historian Carroll Smith-Rosenberg has written, it is construed as “one of the classic diseases of the nineteenth century.”7 Evidence from Ancient Egypt suggests that it was the first mental illness conceived of as uniquely and fundamentally female. The Greek physician Hippocrates was first to use the term “hysteria,” the etymological origins of which point to a very telling definition: uterus. For centuries, wild theories about female anatomy have simmered. In the seventeenth century a theory took root that the uterus—long believed to be the root of every female malady—bounced around the body like a rubber ball, wreaking havoc wherever it settled. Victorian women carried smelling salts to revive them when they swooned: apparently the uterus disliked the pungent odor and would be enticed to meander back to its appropriate place within the loins. Men were diagnosed with hysteria too, albeit comparatively rarely; moreover, physicians, entrenched in essentialist medical ideology, debated whether one could be a hysteric if one’s biology did not include a uterus, the affliction’s perceived locus.8

In 1847, Hollick published The Diseases of Woman, Their Causes and Cure Familiarly Explained; with Practical Hints for their Prevention and for the Preservation of Female Health, a book meant to become a household staple, a compendium for reference when domestic angels were, for obscure reasons, freaking out. Unsurprisingly, he devotes a lengthy entry to hysteria, with the underlying thesis that women are essentially fragile and prone to malady, particularly—but not always!—when their dispositions are emotionally sensitive, and practically everything can be read as a symptom. Predictably, he pins the site of the malady within the tricky and changeable womb:

In regard to the starting point or original seat of Hysteria, there seems to be no doubt of its being the Uterus, which becomes subject to a peculiar excitement, or disturbance, that exerts a wonderful sympathetic influence on the whole system. The Uterus, it must be remembered, is the controlling organ in the female body, being the most excitable of all, and so intimately connected, by the ramifications of its numerous nerves, with every other part.9

But although the uterus was charged as the hub of all feminine maladies and distress, Hollick cautions that there is no feasible way to comprehensively document hysteria’s every symptom. “The symptoms of this disease comprise, if we were to enumerate them all, those of nearly every other disease under the sun,” he writes. “In fact, they are so numerous, so various, and so changeable, that describing them all is out of the question.”10 And yet, he makes a valiant effort, in a passage that is the stuff of dark comedy—for all its absurdity, texts like this one, in which a socially manufactured disease is interpreted as medical fact, have warped women’s lives and clipped their liberties:

The causes of hysteria are as abscure [sic] as the symptoms are diversified. Probably some of the most frequent predisposing causes are, weak constitution, scrofula, indolence, a city life, bad physical and moral education, nervous or sanguine temperaments, the over excitement of certain feelings, and religious or other enthusiasm…Some of the immediate causes are, the first period, suppressed menstruation, late marriage, chronic inflammation of the womb, vicious habits, and long continued constipation. Vivid mental emotions, and excited feelings, may also be specially mentioned, such as anger, fright, disappointment, particularly in love, reading sentimental and exciting romances, and disagreeable, painful, or sorrowful sights. Some authors also suppose there is a hereditary disposition to hysteria, and others that there is a peculiar temperament which disposes to it. It is certain that immitation [sic] has much to do with it, or, in common parlance, it is catching, for very often when one female is taken in an assembly, many others will also be attacked from seeing her.11 (emphasis mine)

Although Hollick’s laundry list indicates, before anything else, that the illness described is illusory—a fantasy of basic feminine subordinacy—he returns to references of heightened affective states, implying both that it is dangerous for a woman to harbor these feelings and that women who are inclined to “vivid mental emotions” are social hazards. A hysterical woman is, above all, an inappropriate one. “She becomes dejected, or melancholy, and will sigh, or burst into tears, and then as suddenly laugh in the most immoderate manner, and without any reason for it,”12 Hollick explains. As he lectures his readers, his tone waxes with urgent castigation: any woman might be a hysteric, but those most likely to become so, he determines, are those whose characters are cracked with moral turpitude:

Women disposed to hysteria are generally capricious in their character, and often whimsical in their conduct. Some are exceedingly excitable and impatient, others obstinate or frivolous; the slightest thing may make them laugh, or cry, and exhibit traits which ordinarily they are not supposed to possess. Like children, the merest trifles may make them transcendently happy, or cast them into the most gloomy despair. Very frequently they are made much worse by seeing that those around them have no real commiseration for their sufferings, and perhaps even think they are not real. A delicate attention, and properly exhibited sympathy, will soothe and calm the excited feelings more than almost anything else.13 (emphasis mine)

Hollick’s account of hysteria never achieves greater specificity, only an increasingly taut strain of stigmatizing rhetoric, connecting states of exuberance and depression with a disposition predisposed to caprice and frivolity—and of course it’s not clear what the doctor considers examples of the latter, besides “reading sentimental and exciting romances.” Indeed, his most precise directions for combating the menace of hysteria corroborates contemporary perspectives on suitable pastimes for the gender:

All kinds of sentimental and romantic reading must be avoided, but amusing books, or travels, and descriptions of scenery may be allowed. Music or poetry, when indulged in to excess, and with those of an excitable temperament, is often highly injurious. More domestic occupation, and less fanciful idling, would prevent numerous disorders in many young females.

These archaic—and legitimately bonkers—theories have been debunked, but the anxiety underpinning them has lingered, rendering female bodies the landscape of a brutal ideological battlefield. The protracted, but ever vicious, reproductive rights debate asks whether a woman is sovereign of her body: Is she free—is she reasonable enough—to treat it as she sees fit, and should that freedom be circumscribed depending on circumstance? And for that matter, how should the body feel to the woman living in it?

It’s through literature that we gain access to Victorian female perspectives, through writers like the Brontë sisters and George Eliot and Elizabeth Gaskell and Christina Rossetti, all of whom, in various modes and means, contemplate the circumstances of women in an age when emotion was so viciously policed and pathologized. It’s stories like Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper” that articulate, with blistering focus, the individual ramifications of widespread hysteria diagnoses, and sensation novelists like Mary Elizabeth Braddon who bear out in their narratives the terror with which Victorian men regarded women, whose bodies and temperaments seemed, to them, irrevocably illegible. In order to account for the fearsome conundrum of women, men resorted to obsessive, stigmatizing taxonomies, legitimized through the medical establishment. Even novelist Thomas Hardy c

onveys remarkable empathy in the famously tragic Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891) in which the titular woman is doggedly shamed and tortured for her desires—and for the potency of her sexual attractiveness, regarded as something of a character flaw whenever it was convenient for men to do so. As we will see, other male writers, Lewis Carroll, for instance, did not share Hardy’s insight into the structural misogyny that could render a woman’s reality a waking nightmare: instead Alice in Wonderland illuminates the anxieties surrounding female bodies that ignited the hysteria craze and conveys the abiding fear that women were, by virtue of biology, excessive in ways that could be dangerous to men if they were not soundly bridled.

Victorian literature reveals and, often, responds to an enduring principle that has since lurked in cultural understandings of femininity: women’s bodies, historical sites of male anxiety and consternation, are not trusted to register maladies in ways legible to the institution of medicine—and we, the custodians, cannot be trusted to accurately represent our interiorities. Perhaps we are Freudian hysterics or hypochondriacs or, to draw on recent conversations surrounding the #MeToo movement, perhaps our real diagnosis is anger, even bloodlust—for one man, or for cisgender men at large. Moreover, through the lenses of fear and prejudice, biological processes like menstruation and childbirth distort and appear dubiously associated with black magic—what sorts of creatures bleed for days without dying? Perhaps we are monsters after all.

Chapter Two

Too Much

Too Much